When Ana Kristiansson joined the KORE Speaker Series from Stockholm, it was immediately clear that this was not going to be a surface-level sustainability talk. Kristiansson is the founder and CEO of Portia, a software platform helping brands manage product development, traceability, and digital product passports. She also runs Desinder, a design agency she has led for nearly two decades.

Through Desinder, she has worked hands-on with hundreds of outdoor and apparel brands, from early-stage startups to global players, giving her a rare view into how products are actually designed, sourced, manufactured, and sold. Her presentation, “Designing for a Sustainable Future: The Power of Circular Thinking,” was a practical, candid masterclass on why the linear “make, sell, discount, discard” model is breaking down, and how circular design can help brands survive and thrive. This is a summary of the key points in her presentation.

The Scale of the Problem, and the Opportunity

The statistics Ana shared were sobering. The world produces roughly 120 million tonnes of textile waste every year, with most garments ending up in landfill or incinerated. Textile-to-textile recycling accounts for only about one percent globally. On top of that, roughly 15 percent of fabric is wasted during the cutting and production process.

But where there is waste, there is opportunity. The global resale market for apparel is already worth hundreds of billions of dollars, while repair, rental, and subscription models continue to grow. Ana emphasized these are no longer fringe experiments. They are proven revenue streams that many brands are already tapping into successfully.

Circularity Is Not One Thing

One of the most useful takeaways from the presentation was Ana’s insistence that circularity is not a single solution. It is a toolbox. Brands can experiment with resale platforms, repair services, rental programs, trade-in or buyback schemes, spare parts and repair kits, upcycling initiatives, or made-to-order and pre-order models. Not every approach will deliver immediate return on investment, but taken together, they build resilience and long-term value.

For smaller brands in particular, Ana encouraged testing one idea at a time, treating each as a business case rather than a full-scale transformation. Circularity, she stressed, rewards iteration.

Designing Products That Last Longer

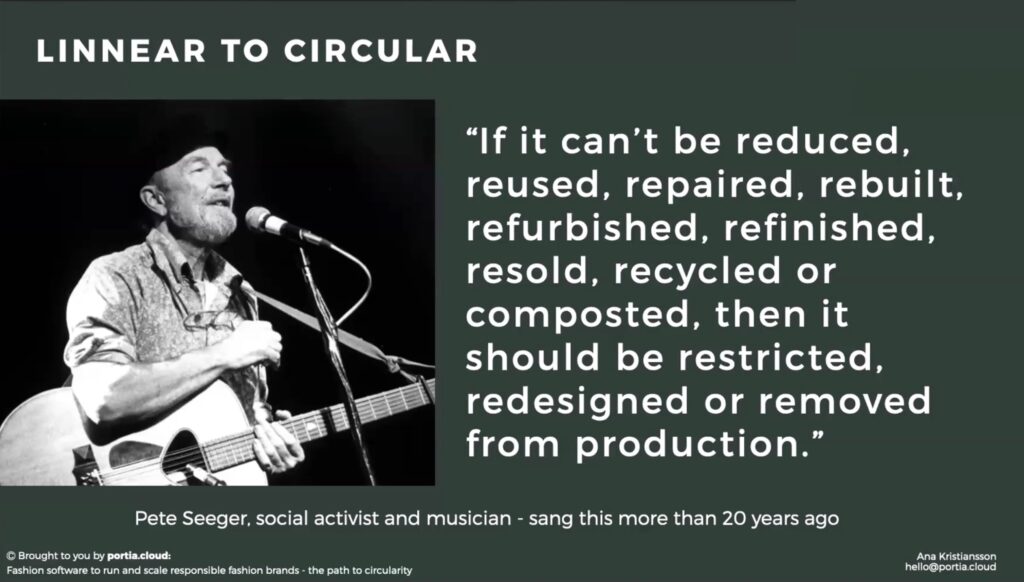

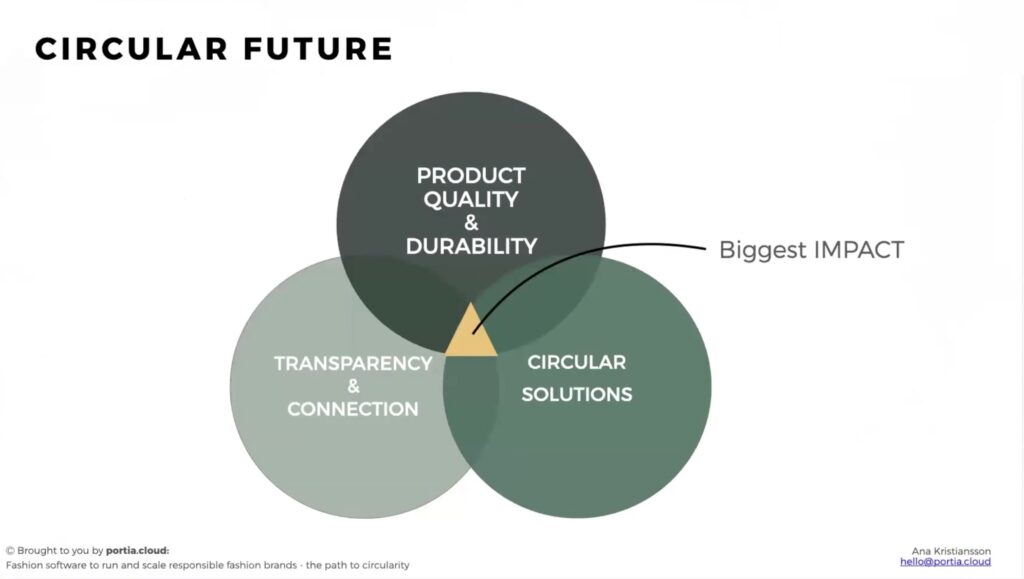

At the heart of circular thinking is longevity. Ana explained that the environmental impact of a garment is driven largely by how many times it is worn. Longevity is influenced by three factors: physical durability, emotional connection, and psychological perception.

Designing for durability means choosing materials, components, and construction methods that match the product’s intended use, not just its price point. It also means understanding details many brands overlook, such as thread type, seam construction, and ease of repair. Designing for timelessness, through classic silhouettes and versatile colours, helps products resist trend cycles and stay relevant longer.

Equally important is emotional longevity. Products that carry stories, memories, or a sense of identity are used and cared for longer. Ana reminded the audience that design is not just functional, it is deeply human.

Designing Out Overproduction

Another recurring theme was designing for demand rather than reacting to excess. Ana challenged brands to take a hard look at their collections. What are the true best sellers? Which products are shelf warmers? If 25 percent of a line disappeared tomorrow, which items would no one miss?

By narrowing collections and focusing on what a brand does best, companies can reduce overproduction, eliminate unnecessary duplication, and improve sell-through. Circular thinking here is as much about restraint as innovation.

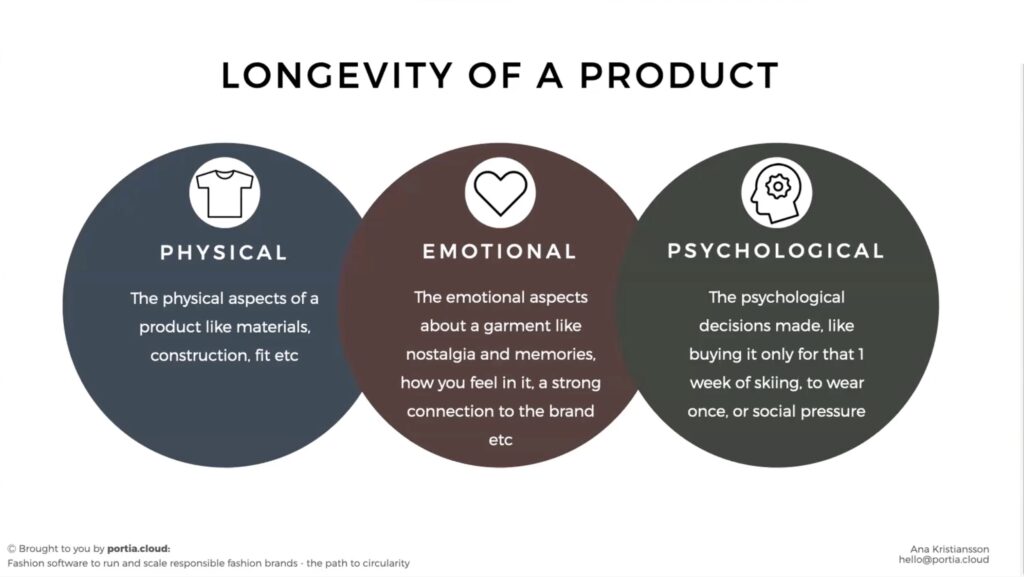

Transparency as a Competitive Advantage

When the conversation turned to communication, Ana was clear: transparency is no longer optional. Eighty-eight percent of Gen Z consumers expect brands to prove their social and environmental claims. Vague language and polished marketing are no longer enough.

She reframed the supply chain as a storytelling engine. Instead of hiding factories behind anonymity, brands can turn traceability data into human stories. Who made the product? Where did the materials come from? What improvements have been made over time? These narratives build trust and are far more compelling than generic product features.

Importantly, transparency does not mean revealing everything. Brands can choose what to share while still being honest and accountable.

Measuring What Matters

Ana closed with practical guidance on tracking progress. Traditional metrics alone do not capture circular performance. Brands should also look at product lifespan, repair rates, warranty claims, dead stock reduction, resale revenue, and material waste reduction. Digital product passports, she noted, are not just compliance tools but a way to build direct, meaningful relationships with customers and gather valuable feedback.

A Call to Be Bold

The presentation ended on a note of optimism. The linear economy was created by people, and it can be redesigned by people. Ana urged brands to be bold, to start small, and to focus on the changes with the greatest leverage. Circularity, she reminded us, is not about perfection. It is about progress, courage, and choosing to design a better system, one product at a time.

KORE Outdoors gratefully acknowledges the financial support of the Province of British Columbia.